There have been no lack of complaints from non-Power 5 schools and conferences, alleging that they are being made to suffer monetarily for matters over which they had no power since the defendants and plaintiffs in House v. NCAA reached a preliminary$ 2.8 billion arrangement deal in May.

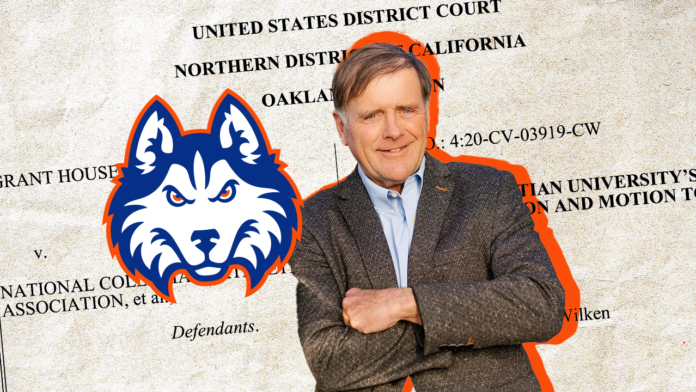

But so far only one organisation, Houston Christian University, has taken the formal–if constitutionally questionable – next step in attempting to block the court’s looming solution. The class of 2, 300 academic students asked a federal court to engage in the case in a seven-page motion filed on June 20. They claimed the situation had” significantly protectable” passions that no party had taken “any move to protect.”

Its request for pleasure comes 16 years after the university, which was formerly known as Houston Baptist, settled a federal antitrust dispute with the NCAA regarding the waiting time for colleges applying for Division I account.

Helping to lead Houston Christian’s situation then, as now, is its anomalous outside lawyers, James Sears Bryant, whose resumé includes professional sports broker, Democratic state representative ( from a Democratic district in Oklahoma ), minor league baseball team user, consumer advocate and Hollywood producer. When it comes to religion, Bryant describes himself as “probably a heretic”, and when it comes to college sports, he’s probably a paradox: a longtime player advocate and NCAA adversary who is also a full-throated defender of amateurism.

” It’s really ]each ] school’s name and likeness that makes college sports so identifiable”, Bryant said in a recent telephone interview, during which he sought to reframe the current debate over House. On Saturday afternoon, it was really entertaining to watch students who were enrolled in the program and compete for prizes at their alma mater. All that is gone”.

Although many have made these points before and have argued in favor of the traditional” college model,” it is interesting to hear them from this man right now.

Bryant had numerous conflicts with the college sports governing body, its strict rules, and the black market it created in his previous roles representing professional athletes. He represented a number of well-known athletes who were the subject of an NCAA investigation for receiving improper benefits. In light of these experiences, or at the very least those that would eventually turn the public, courts, and politicians against the NCAA’s restrictions on athletes earning money, Bryant still supports the role of the” student-athlete” and casts doubt on the legitimacy of the House settlement’s claim to address the billions of dollars lost by college football and basketball players.

These days, Bryant, who is based in Oklahoma, serves as founding partner of the National Litigation Law Group, a 60-employee practice that specializes in credit card and student debt. The firm’s board of directors includes Bryant’s former client, Nick Van Exel, the former Cincinnati Bearcats basketball star who played 13 seasons in the NBA.

In addition to his legal endeavors, Bryant has also stuck a foot in Hollywood, launching a production company, Jesse James Films, in 2020. Bryant has since served as an executive producer on the comedic movies Chick Fight and Hooking Up, as well as the documentary, What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat &, Tears?

Bryant’s relationship to Houston Christian got its own cinematic life. The lawyer recalled having never heard of the private Baptist school before taking it on as a client. He recently succeeded in persuading another small university ( he chose not to name ) to sue the NCAA for the NCAA’s mandatory D-I reclassification wait period, and he was in an airport in 2008.

Bryant struck up a conversation with a nearby stranger who also happens to be an HCU kinesiology professor just before his plane arrived. Eventually, they got to chatting about the NCAA and Bryant’s theory of its antitrust violation. Houston Christian and the association were at the time disputing how long Houston Christian needed to wait for full membership after receiving provisional Division I status in 2007. Based on precedent, the school argued that it should only have to wait three years, but the NCAA had informed them that it was seven.

When the professor returned to HCU’s campus, she passed word about her chat with Bryant along to Robert B. Sloan, the school’s president, who immediately summoned Bryant to Houston for a meeting. With Bryant serving as outside counsel, the school field an antitrust lawsuit against the NCAA in April 2008, decrying its” seven-year group boycott”. The NCAA agreed to give Houston Christian full D-I membership in 2011 as part of a settlement, allowing all of its athletic programs to be eligible for NCAA postseason play.

In a phone interview, Sloan, who continues to lead HCU, gave Bryant much of the credit for keeping the school’s D-I dreams alive.

” We were about to give up ]after ] the NCAA said you ca n’t get in”, Sloan said. ” They were going to wield their power”.

Sloan and Bryant have maintained contact over the years and claim to have been on the verge of filing a second antitrust lawsuit against the NCAA in the mid-’10s as a result of the association’s adoption of a new governance structure that gives the five wealthiest leagues greater autonomy. Loan publicly opposed the changes, but the school ultimately kept its legal standing dry.

” ]Bryant ] and I were ready to go”, Sloan said,” but I could n’t have done this without my board’s approval”. Bryant, meanwhile, has continued to serve HCU in other ways.

He and his wife established an endowment five years ago to pay HCU’s head men’s basketball coach salary. When Bryant was asked what made him want to donate those kinds of resources to a university that was n’t even close to his alma mater, he responded,” Because of amateurism.”

Bryant cast HCU’s recent effort to intervene in the House case as part of a larger, yet deeply personal, battle to preserve the future of small, liberal arts education in America. A self-described’ D ‘ student in high school, Bryant credits much of his success to the” transformative experience” of attending a small liberal arts school—in his case, the now-defunct Phillips University in Enid, Okla. —after a two-year stint in community college. He then pursued a law degree at SMU, launching a career in sports law.

In the late 80s, Bryant, then a newly minted lawyer, was retained by Oklahoma State star wide receiver Hart Lee Dykes, who was being investigated by the NCAA for accepting under-the-table payments during his recruitment. Dykes ‘ half-brother, Todd Chambers, was a college friend of Bryant’s at Phillips University.

At Bryant’s urging, Dykes agreed to a controversial—and nearly unprecedented—deal with NCAA investigators, in which he was given immunity from losing his athletic eligibility in exchange for spilling the beans on several programs, including his own. The player’s testimony led to Oklahoma, Illinois, Oklahoma and Texas A&, M all being put on NCAA probation—and Dykes being publicly pilloried for years to come.

What should a typical attorney do when a client requests information about where the car and cash were taken by the NCAA? Bryant said. ” I say,’ You tell the truth and cut a deal.’ I guess I was pretty naive. I did n’t understand the repercussions of what was happening.

Before the upcoming NFL Draft, Bryant stepped down as wide receiver after the New England Patriots selected him to represent Dykes. In response, Bryant filed a suit against Dykes, claiming the player had breached their representation contract and owed nearly$ 30, 000 in unpaid loans. Bryant ultimately decided not to pursue the claim because he insisted that his lending only occurred after Dykes had left college. Chambers, Dykes ‘ half-brother, would later work at National Litigation Law Group, and still serves on its board.

In the mid-1990s, Bryant moved to Washington, D. C., to join ProServ, the once-dominant sports management firm, where he ran the basketball division following David Falk’s breakaway with Michael Jordan. Among Bryant’s clients was Marcus Camby, the No. 2 pick in the 1996 NBA Draft. After later being found to have broken NCAA regulations, Campbell admitted to accepting cash and jewelry from an agent while he was a student. UMass ‘ Final Four appearance was later cancelled by the NCAA and the university was forced to pay back the money it had raised from its tournament bid.

Because the majority of the corruption in college sports is not over the cars and things you saw in the Camby deal, it is over lunch money, over a mother who needs a house payment paid, Bryant said,” but what we are doing is eliminating amateurism as players should not have as restrictive as the rules [the NCAA ] had,” Bryant said in a statement.

Thus, Bryant contends the House case is not an engine of progress.

He claimed that “higher education leaders are incredibly progressive in the classroom but utterly reactionary about their own institutions.” ” They are afraid of change”.

To him, the proposed settlement only furthers that conventionalism.

” It does n’t take thinking out of the box to settle a case”, said Bryant. People consistently settle to avoid liability and controversy rather than adopting corrective positions in disputes is one of the biggest issues with the legal system. These]damages ] did not happen. Nobody took$ 2.8 billion ]from athletes ] … I am a huge college football fan, but tell me: Who has had$ 280 million a year taken from them”?

Sloan, the HCU president, says the school’s board was completely on-board with the latest legal action. Houston Christian is the only school leader who is currently advancing the small-school argument in court, but Bryant and Sloan both claim to have heard from a number of other school leaders who have indicated they will join the fight.

” Because we have low resources, we could n’t afford to have a big, massive lawsuit to take on deep pockets”, said Sloan. ” All we are asking is that you can sit at the table. It raises all the obvious problems with what is wrong with college athletics, in my opinion. They are threatening amateurism. They are allowing our mission to be subverted. The dog’s tail is wagging.